Up on the hill overlooking Kushiro Marsh, everyone was taking deep breaths. The wind was low and vast, flat wetland spread out below us. There was woodland made up of reeds, sedges and Japanese alder, large, meandering rivers and a cloudy sky hanging low over the scene. It was worth the trip just to see this incredible view. I prayed that this scene would never change, the world of humans may undergo constant transformation, but nature is eternal.

Moving through the marsh, the view opened up as I arrived at Lake Toro. Thousands of years ago, it is said that this area used to be a sea, but now its freshwater is home to Sakhalin taimen and char. One of the locals told me that grey heron nest in the nearby woods and the entire marsh reverberates with their calls when the chicks emerge in early summer. Looking over to the heron’s forest from Lake Toro, I could see the Nitay To Museum, the name of which means “forest and lake” in the language of the indigenous Ainu people.

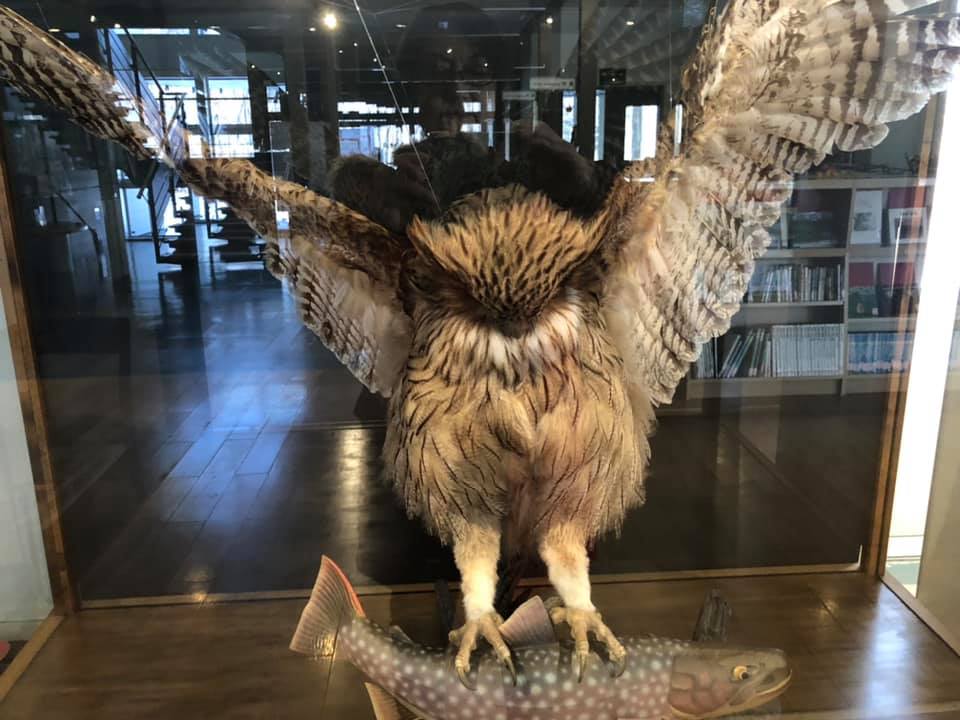

The museum tells the story of the gratitude of the people who lived in and around the woods and lakes of the marsh over the course of 10,000 years. They lived off what the marsh gave them; the animals they hunted, the fish they caught, and the plants they harvested. The tools used for these tasks were also invaluable, obsidian used for harpoons was transported from distant areas and was used with great care until the blade became chipped and misshapen. Those who passed away were carefully buried together with tools and ornaments in graves lined with bright red iron oxide. The souls of the tools that had served their owner so well were then sent to the next world with a ritual of thanks. This story of gratitude continued as the tools used in life transformed through the ages from stone, to earthenware, to iron. The Ainu people regard all objects and phenomena in the natural world as gods, and perform rituals to express their appreciation. Even the tiny water chestnuts that live around Lake Toro are not neglected in this show of gratitude to the gods.

However, humankind began to interfere around the mid-19th century and the story changed to one of conflict. Following political upheaval in central Japan, those who had opposed the new government were sent far north to prisons in Hokkaido. A prison was constructed near the forest and lake, housing as many as 1,400 prisoners at one time. Later, the prison facilities were converted to military horse training facilities. The rearing of war horses was entrusted to local pioneer farmers, who had been struggling in the wetlands for a long time. Looking after these horses was followed by cattle breeding, which in turn paved the way for dairy production.

During Japan’s economic miracle, plans were established to fill in the marsh and turn the area into factories and farmland. As land reclamation began, the lake was polluted and fish stocks were depleted. In the marsh, animal nests and bird nesting sites were destroyed, and red-crowned crane chicks died one after another. Unable to ignore the worsening situation, local fisherman and dairy farmers joined the fight to protect the marsh. There was a growing sense of danger that the marshland’s natural beauty, which had been taken for granted for so long, would soon be destroyed.

After decades of struggle, the marsh has been declared a national park and is now protected. It is not just down to nature that the same flowers bloom in Kushiro Marsh every year. Over the generations, the appreciation and respect held by the people for the life of the marsh has meant that when external forces sought to destroy it, they always fought to defend its forest and lake.

(This article was written in a project involving our company sponsored by Hokkaido District Transport Bureau)

RELATED ARTICLES

-

The Odori Park in Sapporo

-

Double-flowered cherry tree are beautifully blooming.

-

The spectacular night view of Sapporo

-

Marimo at Lake Akan

-

What is a trip for kids?

-

Beautiful Japanese Crane Tancho in Kushiro, Eastern Hokkaido

-

Ecorin Village in Eniwa: A Town of Flowers and Ecology

-

Pleasurable Farming Tours in Hokkaido

-

Experience Contemporary Ainu Art at the Foot of Mt.Hakkenzan

-

The present-day Ainu and Iomante -from the story of th...